Need something? Just hit control+P

From body organs to houses on other planets, from meals to shirts, tea mugs to bridges: 3D printing is already starting to revolutionise the way things are made and their accessibility.

So much so, that the presence of this technology has already started raising eyebrows. For good reasons and not so good ones.

The Koran, just like the Bible, Sumerian, Greek, Chinese, Egyptian and Inca mythology, as well as many Amerindian myths tell about the crea- tion of man from clay, dust or mud.

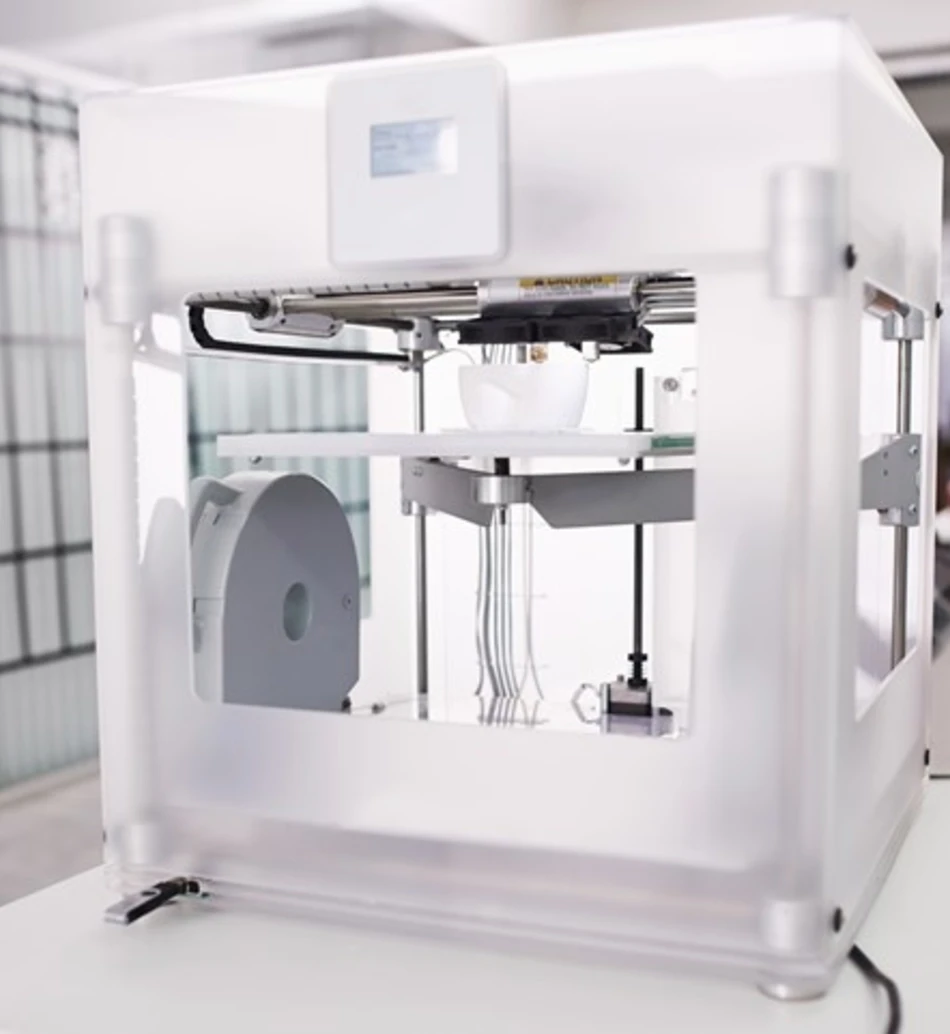

Watching a 3D printer in action reminds us without doubt of this fundamental parable. From raw material, little by little, something new appears and comes to existence.

Born in the eighties, the process is more self- explanatory under its other name: additive manufacturing. A 3D model is created by CAD, virtually decomposed into fine layers and built up by a machine layer upon layer. A variety of techniques are used (stereolithography, fused deposition modelling, selective laser melting…), but the principle is the same.

At first limited to rapid prototyping, 3D printing has been developing very fast. It is now pos- sible to print in plastic and polymers, but also in metal (titanium, gold, silver, bronze and steel…), wax and sand. Even using food components and biological materials.

The precision of the printers and the quality of finishing have improved so much that it is possible to print finished parts for profes- sional applications (audio headsets, glasses, jewellery) as well as for the most demanding applications, such as the automobile and aero- space industries.

There’s no limit to the size either: additive man- ufacturing can produce furniture and decora- tion. In 2017, the MX3D robot will “print” – on its own, in mid-air – a steel bridge over a canal in Amsterdam. It is also possible to print houses.

These past few years, the same tectonic shift has been taking place in 3D printing as hap- pened in the world of electronics in the eighties: it’s becoming personal.

“Office” printers are proposed by Stratasys (MakerBot) and 3D Systems (CubeX), two leaders in professional solutions. Less and less expensive, becoming user-friendly, they have started to become accessible to the gen- eral public.

Individuals can also use printing services offered by major retailers like Auchan in France or Ama- zon and Staples in USA. They are also capable of printing the required objects through “factories in the cloud” like Sculpteo (see our interview with its founder on page 20) or Shapeways.

The global market for additive manufactur- ing has been also gaining a new dimension: in mid-2014, Research and Markets estimated it at

2.3 billion and forecast a growth of up to 8.6 bil- lion by 2020. According to a study conducted by Siemens, 3D printing would be 50% cheaper and 400 times faster by then.

These numbers prefigure the ultimate future of this technology. A future that will be part of our day-to-day life. Companies will produce complex parts without the need for suppliers. Designers and inventors will produce their own creations without having to convince manufac- turers first. There will be self-service 3D print- ers in supermarkets. Families will print everyday objects or even their meals.

A groundswell? Economist and futurist Jeremy Rifkin believes so. He thinks that 3D printing will be one of the pillars of a new industrial revolu- tion. The USA believe in it as well, seeing it as an

opportunity to create jobs in sectors relocated to Asia. Barak Obama promoted 3D printing during his 2013 State of the Union address. In Europe, governments support many Fab Labs, these collective factories using 3D printing to a great extent.

Like every revolution, 3D printing also has its dark side.

The highly publicised 3D printed gun by a young Texan in 2013 and its files posted on the internet has given a first glimpse of a poten- tially anarchic future.

“Classic” industry has adopted 3D printing while feeling concerned about having the same expe- rience as with MP3 and the music industry – a gravedigger of copyrights. The illegal production of objects (starting with figurines from films, TV series or video games) has been growing. Cease and desist letters have become common practice.

With 3D printing, the future hits the present. The medical industry illustrates this shock particu- larly well (see pages 18-19). In Europe, in Asia, as in the USA, we have surpassed the problems of custom prostheses or implants. Living tissue printing is being developed. At the end of 2014, Organovo marketed the first human tissues, produced on an in-house 3D printer.

How about the next step? It is on its way: pro- ducing functional organs on request!

Print a heart, implant it in a chest, see it beat. 3D printing will recall more than ever Divine creation.